How To Get Out Of A Civil Lawsuit

Claims of employee mistreatment are center stage, between sexual harassment and discrimination scandals in the TV business and in Silicon Valley, and now the Trump Administration's retrenchment on LGBT protections in the workplace and banning of transgender people in the military.

But according to a new analysis of employment cases by legal research service Lex Machina, very few employees who file federal job discrimination, harassment, and retaliation claims even make it to court, and only 1% of those claims eventually succeed in court. A majority of cases are settled, employers prevailed on summary judgment roughly 13 percent of the time, and only 192 damage awards out of 72,000 cases included punitive damages.

The Long Road To Trial

Employees who gather the courage to take action against their employer begin by filing a charge with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, typically within 180 days from the time the discrimination took place. Through a fact-finding process, the EEOC decides whether or not a charge is strong enough to take to trial. An overwhelming number of allegations do get the EEOC's Notice of Right to Sue, which is a thumbs-up to proceed.

But few of these cases actually become lawsuits. For fiscal year 2016 (Oct. 1, 2015 through Sept. 30, 2016), employees filed 97,443 charges, and the EEOC issued 81,129 Notices to Sue (83.3%), according to records provided toFast Company. For that same period, meanwhile, Lex Machina counted only 7,239 cases that went onto lawsuits—less than a tenth of the charges EEOC gave a green light to over the same time frame.

Lex Machina also examined data on the lawsuits themselves, and found an even smaller fraction of victories for plaintiffs.

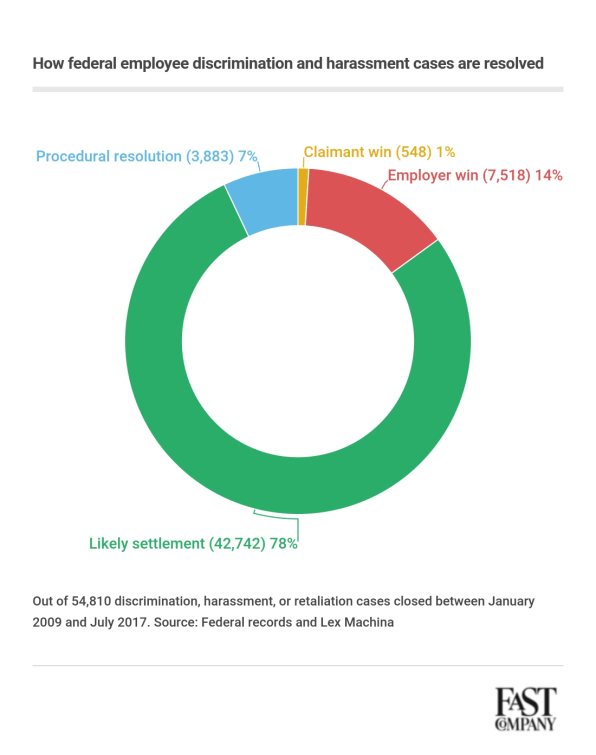

Over an even longer period—from January 2009 through July 2017—Lex Machina found that of 54,810 cases that were filed and closed, employees bringing the suits won just 584 times in trial, or about 1% of the total. Employers won 7,518 cases, about 14%. Another 3,883 cases, or 7%, were settled on procedural grounds, mostly dismissing the employee's claims.

What happened to the rest of the cases? No one knows for sure why 78% of cases were dismissed by either the employee or both the employee and employer, but Lex Machina assumes that almost all of those 42,742 cases were settled. But there is no legal requirement to file the terms or even publish the existence of a settlement, so it's impossible to know for sure how these cases panned out.

Most settlements probably awarded money to the employee, according to Brian Howard, Lex Machina's legal data scientist. But that doesn't mean the settlement was a win for the employee.

"We don't know how much money, what other terms the employee had to agree to, how much they originally sought, how often personal circumstances force the settlement, whether they got any feeling of vindication, etc.," Howard wrote in an email. "Any settlement amount would likely have to address substantial legal fees, so a plaintiff's actual recovery might be small."

It's not clear why so few employee charges move on to court. One reason may be because the costs of litigation to plaintiffs are often far higher than the actual damages. Plaintiffs, especially those newly out of a job, may be more willing to take a settlement than to pursue a costly and lengthy court trial. Or the cases may not be lucrative enough for an attorney to take on, says Howard.

Only rarely does the EEOC itself bring a case on behalf of the employee–usually for cases that have wide-ranging significance. For instance, the EEOC just sued Time Warner Cable and Charter Communications, charging them with firing an employee over her disability, in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

EEOC said its legal staff resolved 139 lawsuits and filed 86 lawsuits alleging discrimination in fiscal year 2016. In total, it recovered $482 million for victims of discrimination, including $347.9 million recovered through mediation, conciliation, and settlements; $52.2 million obtained through litigation; and $82 million for federal employees and applicants.

EEOC has also pursued several LGBT related cases. But the Justice Department's assertion last week that LGBT people are not covered under sexual discrimination laws—the same day President Trump announced that transgender people would be barred from the military—could be just the beginning of changing policies and priorities at the EEOC. Many top posts are being filled with Trump Administration appointees; and while funding has stayed the same, the White House Office of Management and Budget has ordered a reorganization of EEOC that may portend future cuts. (The Commission's Acting Chair Victoria Lipnic described this likelihood in a recent interview.)

The Reasons People Sue

Discrimination claims make up the majority of complaints that go on to lawsuits, at 87%. Several U.S. laws protect employees against discrimination; Title VII of the U.S. Civil Rights Act of 1964, for instance, prohibits discrimination based on six criteria. They are, in order of number of EEOC complaints: race and sex (the vast majority), national origin, religion, and color. Another law, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967, prevents discriminating against people over 40 years old. Other laws prohibit discrimination based on criteria like disabilities or being pregnant.

In December 2012, EEOC concluded that Title VII's prohibition of discrimination based on sex includes discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, and it began tracking the number of cases a month later.

The number of cases based on sexual orientation has grown, up to 1,768 for 2016. Most cases (1,114) were found to not have reasonable cause, and another 282 were dropped for "administrative" reasons, like employees failing to follow through. Just 279 cases, about 17%, had some type of favorable outcome for the employee making the charge, with $4.4 million in awards.

Some of the employees may still have pursued a lawsuit, but Lex Machina doesn't have data on this. "LGBT status is not explicitly protected in the employment context by federal statute, and we track by federal statute," says Howard.

Currently, the Trump administration is at odds over LGBT discrimination. The EEOC filed a brief affirming its LGBT policy on June 23 in the case of a New York skydiving instructor, who claimed he was fired for being gay. It was in this same case that the Justice Department filed its own brief on July 26, writing, "The essential element of sex discrimination under Title VII is that employees of one sex must be treated worse than similarly situated employees of the other sex, and sexual orientation discrimination simply does not have that effect." It's unclear how the rival interpretations between the Justice Department and EEOC will shake out.

Related: Toxic Workplaces Will Persist As Long As Fairness Is Just A Matter Of "Compliance"

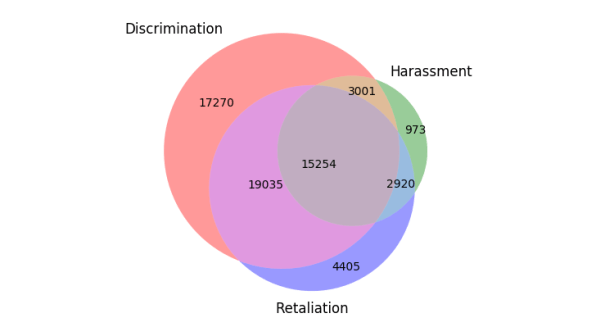

The second largest category of cases, after discrimination, is retaliation, such as getting fired or demoted for complaining to the employer or the EEOC about discrimination: These represented 66% of all claims. Claims of harassment, including sexual harassment, make up 35% of legal cases filed.

If you're wondering why those shares add up to over 100%, that's because many cases fall into more than one category: About half the cases filed since 2009 were for both discrimination and retaliation.

Who Gets Sued The Most

Based on an analysis of cases between 2009 and 2017, Lex Machina has a rough idea of which companies and government agencies have been sued the most. The most commonly named defendants, listed alphabetically, are:

- AT&T

- Bank Of America

- Boeing

- CVS Pharmacy

- FedEx

- Home Depot U.S.A.

- JPMorgan Chase Bank

- Life Insurance Company Of North America

- Sears, Roebuck And Co

- Target Corporation

- United Airlines

- United Parcel Service

- Walmart Stores

- Walgreen Co.

- Wells Fargo Bank

Notice the absence of Silicon Valley companies. Despite all the attention on sexual harassment in the tech sector, so far there have been relatively few legal actions brought by its employees. That could be because most tech firms are smaller than the industrial and commercial giants listed above.

Compared with tech company workers, most of the employees of larger American corporations can face a heavier burden when bringing discrimination or harassment suits. For instance, women in lower-paying jobs who are often subject to harassment have a much harder time fighting against it, since they don't have the means to risk leaving or losing a job, as FiveThirtyEight documented.

The most-sued government agencies are:

- City Of New York

- City Of Philadelphia

- District Of Columbia

- New York City Department Of Education

- United States Postal Service

Sometimes defendants are listed by the name of the person who runs the company or organization being sued. There may be even more cases against the Postal Service, for instance, since three Postmaster Generals–Patrick R. Donahoe, John E. Potter, and Megan J. Brennan–are also on the most-sued list. (In addition to his tenure at the Post Office, John E. Potter now heads the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority.)

The United States Veterans Administration is also probably a major defendant, as Veterans Affairs secretaries Eric K. Shinseki and Robert A. McDonald made Lex Machina's list. The Department of Justice is likely pulled in, given the high number of suits against former Attorney General Eric H. Holder, Jr, and the U.S. Army is implicated in suits that name Secretary John M. McHugh.

In the end, it's hard to know how well the court system is working to protect employees from unfair treatment. It's hard to know, for instance, of those cases that are ultimately settled, how many do justice to the employee? For all the data the EEOC and Lex Machina have collected, they show how much we still don't know.

How To Get Out Of A Civil Lawsuit

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/40440310/employees-win-very-few-civil-rights-lawsuits

Posted by: penafactere.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Get Out Of A Civil Lawsuit"

Post a Comment